Rosh Hashanah 5785

This year has changed my relationship to what it means to be Jewish.

Every year, during the High Holidays, I give a sermon, in one version or another, making the case for getting more deeply connected to Jewish communal life.

I make this case because I genuinely believe in it. I have felt the way that being immersed in Jewish life brings me a sense of meaning, of purpose, of connection, of holiness to me, and I want to share this experience with you, inviting you to explore more deeply, continuing to immersing yourselves, continuing to experience the spiritual riches of what immersing ourselves in Jewish communal life has to offer.

I have primarily built this case around two pillars: one pillar is community and the other is spirituality.

Community: We live in an increasingly isolated world, where researchers speak of an epidemic of loneliness. Sometimes the more hyper-connected we are online, the more our screens serve as filler, papering over the more profound connections our souls truly need. Jewish communal life fosters real, personal connections, zagging when the rest of the world zigs. As I’ve said in the past, come here for any Shabbat service, Friday night or Saturday morning, and after services the social hall is bustling like a high school cafeteria, minus the cliquishness and social awkwardness. (Okay, still with some occasional moments of social awkwardness). I watch relationships flourish here, across the age spectrum: kids running around together after services, adults making new friends in a chapter of life they might not have thought possible; I witness visits from community members to people’s homes to drop off food when someone is sick or to attend a minyan when someone is grieving. Jewish communal life fosters communal connections that are truly profound.

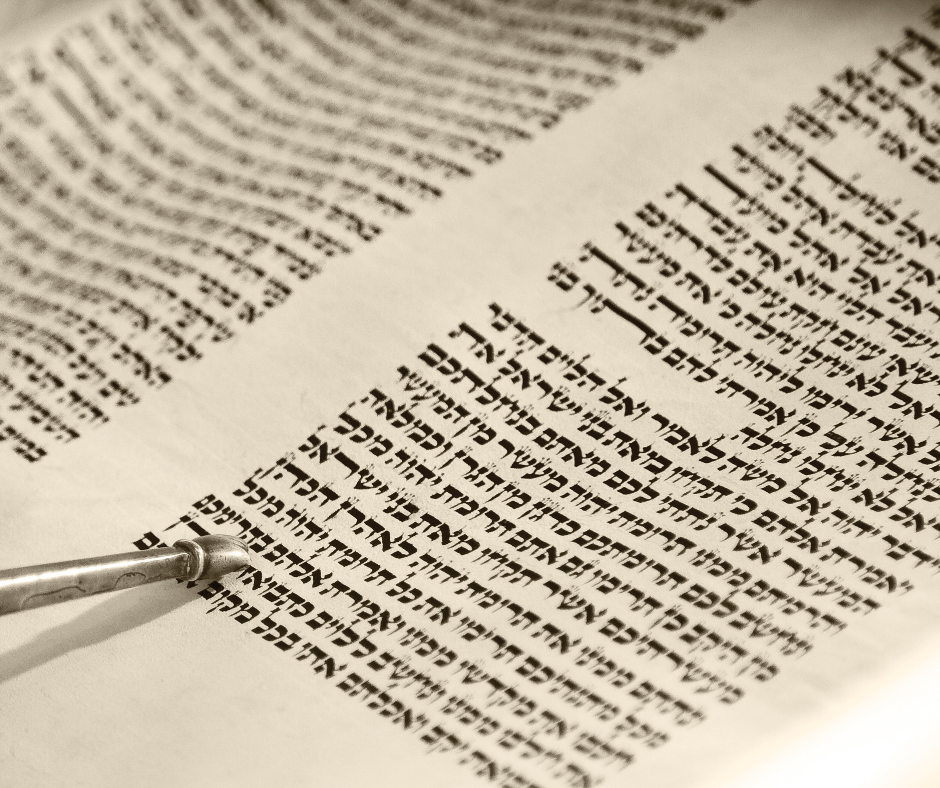

Spirituality: Synagogues like Society Hill Synagogue hold space for engagement with, for exploration of, for forming a relationship to, the Divine, to God, to Hashem — to whatever we might call the Source From Which We All Flow. The word Yisrael, Israel, after all, comes from the story when our ancestor Jacob wrestled with a Divine Figure — Yisra-el: to wrestle with the Divine. One of the pillars of the case I make for why to engage more deeply with Jewish communal life, is that it holds space for a capacity to wrestle with God, to explore our relationships with God, to serve God — even if we don’t know exactly what that means, or in what respect we should serve, or how to explain the world’s brokenness. For me, spirituality can serve as the glue to help piece it back together

Community and spirituality have been the two compelling reasons, in my view, upon which to base the case for more and deeper engagement with Jewish communal life like that which takes place here at Society Hill Synagogue.

But there has been something missing here in my case for this immersion, and it wasn’t until the events of the last year, sparked by the horrors of October 7, 2023, that I’ve begun to explore that missing piece.

I have had, in many respects, the reverse experience of being Jewish from most of you in these pews. The most common descriptor I encounter when speaking to other Jews in relationship to their Jewishness is not Conservative or Reform or Orthodox; it’s the phrase — and you can probably say it with me — “culturally Jewish but not religious.” “I don’t know what to do with the whole ‘religion’ thing,” people say to me, “but I feel some sense of connection to my Jewishness, whatever that is.”

As I say, I’ve had, in many respects, the reverse journey. My father was a rabbi. A deeply religious, deeply spiritual man, the son of first generation Jewish-American immigrants, the children of refugees from Russia. His religiosity, his spirituality was seared into my soul at an early age, perhaps from birth. I see it as one of the great gifts of my life, and I try, over the course of sermon after sermon, to share that gift with you.

This is not that sermon.

As many of you know, my father died suddenly when I was very young. I was seven and my two sisters were four years old and one month old respectively.

So we were primarily raised by my mother. My mother found Judaism through my father, having become Jewish after they met. Judaism lit a candle in her soul. The wick had been there, but it needed a spark. Judaism was this spark, igniting a flame. Her faith then carried us through the next challenging chapter of our lives.

What was less familiar to her, and therefore what I did not grow up with to the same extent, was the piece I discovered to a deeper extent after October 7.

We sometimes understand our Jewishness as our religion. It’s the thing we engage with when we want to talk to God, or when we are encountering a meaningful life event like a birth, a marriage, a death; or when we want to give a basic explanation of why we are here.

But as we know implicitly, being Jewish is not just about having a religion. It’s about having a story; it’s about being part of a people that has found itself far-flung across the globe and yet connected through shared language, shared history, shared reference points—a shared understanding of a journey through time.

After October 7, the experience of being Jewish in America, in a more pronounced way, became not just about religion, a part of ourselves that can be relegated to a private sphere. After October 7, no matter where you stand on the war and conflict that has ensued, the Jewish parts of our identity, or of the identity of our loved ones, have become centered like never before in our lifetimes.

Here in Philadelphia alone, whether it was at protests outside of an Israeli restaurant, accusing the restaurant of genocide; or vandalism at a Jewish after school program for kids, with the words “free Palestine” sprayed on its windows; or grafitti with both slogans — “free Palestine” and “stop the genocide” — spray-painted at my five-year-old daughter’s bus stop on the way to her Jewish day school, under these circumstances, we’ve become more and more clear that our Jewish identity does not start and stop at the synagogue doors or the doors of our home.

I want to be very clear: As of today, I have very little fear for my physical safety as a result of my Jewish identity. It remains far more dangerous to live in poverty in North or Southwest Philadelphia than it does to be a Jew in America, and that danger, that poverty, should call out to us, too. I’m betting whoever spray painted that bus stop had no idea who gets on that bus or where it goes.

But we are living in a moment where significant populations in parts of our society that we revere—higher education, our K-12 schools, — have started to say to the Jewish people, “Yes, you can be Jewish; of course you can be Jewish… But could you maybe tone down certain parts of that Jewish identity. Could you check certain parts of that Jewish identity — namely your relationship to Israel and to Zionism — at the door?”

“To the extent you see those as part of your Jewish identity” — some voices say, those parts being your relationship to the state which has been a foundational part of Jewish self-understanding in the 20th century, the state that was built out of the ashes of the Holocaust as a safe haven for Jews returning to their ancient homeland, albeit, yes, on land which another people had also come to inhabit and call its home, and granted yes it being a state, like all states, which also inflicts costs on other peoples as it battles for its safety and security — “to the extent you see your relationship to Israel as part of your Jewish identity,” these voices say, “could you could you quiet that part, silence that part, or better yet, could you condemn that part, before you enter into the broader conversation?”

None of these intimations are to suggest there shouldn’t be a robust debate about this war and all wars. About the future direction of the state and how we feel about it. About navigating a future for two peoples in a small land. About a current government that lets extremists run wild. That debate is totally fair game.

But what I’ve encountered since October 7, is that in some spaces my Judaism is welcome, but my Jewishness is not: not my relationship to the whole of my people, the whole of my culture, the whole of my story.

And it’s caused me to reflect.

While it’s negative pressure that led me here, there is a positive development that has resulted.

For me, the missing piece of the case I’ve been articulating for immersing ourselves in Jewish communal life is to connect to this Jewish story.

That is, part of why I believe it’s valuable to foster a deep relationship with Jewish communal life is not just because it holds space for us to foster connections in community, though we couldn’t live life without those connections, and not just because it empowers us to hold space for wrestling with the Divine, though I believe that’s a deeply significant, perhaps the central, part of life; but because it enables us to locate ourselves within the Jewish story, to root ourselves in that story, and to take upon ourselves the responsibility of helping to author the next chapter of that story, which is not yet written.

Now, why do I believe this is so important?

For some generations, perhaps the older generations, it is self-evident: being Jewish is core to who we are and to how we experience the world; of course we’re going to locate ourselves in that experience and see the world through that lens.

For others, oftentimes for younger generations, it is not so self evident: being Jewish might be a more marginal part of our identity, if it is present at all. And besides, why focus on what divides us? Are we not all just human beings, trying to navigate our way forward in the world? What value is there in locating our experience so centrally in the story of one people?

On one level, I agree with that. The Jewish story is not the only influence in our lives. Many of us have a multitude of identities, influences, languages, all worthy of being embraced; why not focus simply on our shared humanity, rather than on any distinctive story?

And yet, in thinking about this question, I can’t help but think about this shofar. There is a teaching on the shofar by Natan Sharansky, the Soviet dissident, who spent nine years in a Soviet prison for trying to help Jews escape repressive regimes in the Soviet Union. About the shofar he says, let’s take the broad end and try to blow in it: nothing happens. How about the small end? There, the call of the shofar rings loud and true.

And yet, in thinking about this question, I can’t help but think about this shofar. There is a teaching on the shofar by Natan Sharansky, the Soviet dissident, who spent nine years in a Soviet prison for trying to help Jews escape repressive regimes in the Soviet Union. About the shofar he says, let’s take the broad end and try to blow in it: nothing happens. How about the small end? There, the call of the shofar rings loud and true.

We ground our contributions to this world from the focal point of our particular experience, our particular communities, our lived realities, deeply rooted. We get our bearings in the world through the fabric of tight-knit communities who can relate to one another deeply through shared stories, shared understanding, shared learning. We then work outward, as a part of that story, from that strong foundation, to bring about a collective redemption for all, recognizing that we are all created in the Divine image. Both ends of the shofar are essential—the small, intimate end into which we blow; the broad, transcendent end, out of which it rings, pure and true. We start from the personal; we reverberate out to the universal.

To put it another way, two things can be true at the same time: (1) every single person on this earth is equally sacred in the eyes of God. Jewish, Christian, Muslim; Israeli, Palestinian, American. No life is more valuable than the next. Period. Full stop. No debate.

And (2) Each of us has real, intimate relationships, real intimate communities, that shape who we are. I have a wife and two daughters who have helped me grow in ways I never thought possible. I have a mother and two sisters who helped form me as I navigated my way through the world, relationships I deeply cherish. Being human means we can recognize that everyone is fundamentally equal, equally worthy of love, and that we each in our respective spheres have intimate relationships to particular people, particular peoples, particular communities. It is in the crucible of those relationships, those communities, that we experience our most sacred connections, in which we learn about who we are and in which we learn what it means to be human and to love other human beings in turn. Those intimate relationships should then awaken within us the knowledge that every person on earth, every people on earth, has the same divine spark within them. Every person is worthy of the empathy we discover in our own relationships, our own children, seeing their faces in the children of others. Muslim and Jewish; Palestinian and Israeli.

The Jewish story is not a story that is inherently superior to the stories of other peoples. The Jewish people is not a people that is superior to other peoples. That should go without saying.

But the Jewish story does have something going for it that no other story does. It’s ours. It’s our story. As a synagogue community, here at Society Hill Synagogue, the Jewish story is our story, and I think a sacred part of life is to keep ourselves rooted in who we are and where we come from, roots which take in nourishment, allowing ourselves to flourish, growing sheltering branches in the sky, and roots which keep us anchored in the solid ground when the winds blow us this way and that. Not rigid, but rooted. Ongoing engagement with our story, I believe, can give us that.

Before I go any further, I need to do a piece of unpacking.

Who’s “our”? Whom does that “our” include?

Well, potentially, it includes everyone in this room: everyone in this sanctuary, everyone on Zoom, everyone listening right now.

For starters—and only for starters—it includes everyone who is Jewish. If you’re Jewish, the Jewish story is your story. Doesn’t matter how many commandments you observe or don’t observe. How many times, or how few times, you go to synagogue a year. Whether you were Bar or Bat Mitzvahed or not. If you’re Jewish, the Jewish story is your story. Period.

So who is Jewish? For starters, anyone who has at least one Jewish parent. It’s true, different denominations have different standards: the Orthodox and Conservative world say it has to be your mother who is Jewish, the Reform and Reconstructionist world say if either parent is Jewish, you’re Jewish. Society Hill Synagogue has for decades taken the more expansive definition, if either parent is Jewish you’re Jewish. But in any event, when we’re talking about whose story is the Jewish story, I think it’s safe to say that if either of your parents is Jewish, that means the experience of the Jewish story is a part of you. It’s part of what led to where you are today. The Jewish story is your story.

But it’s not only your story.

So, too, if you chose to be Jewish, immersing yourself in a mikvah, taking on the Jewish story as your own. The Jewish story is just as much yours as anybody else’s. This was a practice made famous by Ruth, the moabite woman, who, when her Israelite husband died, told her mother in law, who was grieving her son, “wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16). The Jewish story understands King David, and therefore, the moshiach, the ultimate redeemer, to be a descendent of Ruth, thus putting those who chose to be Jewish on equal footing with all who were born Jewish. If you, like Ruth, chose to be Jewish, you’re Jewish. Period. The Jewish story is your story.

But it doesn’t end there. How about those who are lovingly supporting Jews, even if they’re not Jewish themselves? How about the non-Jewish father of two Jewish children, each of whom he’s supported to go up on the Bimah to celebrate becoming B’nai Mitzvah, alongside their Jewish mother. You think he doesn’t have a stake in the Jewish story?

Or the non-Jewish husband who has sat dutifully alongside his Jewish wife at high holiday services for decades, unable to imagine the year without these rhythms, even if it’s not his faith tradition. Does he not have a stake in the story of the Jewish people?

Or the mom, who never converted but who reads the Hebrew School emails more diligently and shows up more consistently than the Jewish father. You think she isn’t deeply invested in the Jewish story?

When Israel left journeyed from Egypt into the wilderness on their way to the promised land, it says וְגַם־עֵ֥רֶב רַ֖ב עָלָ֣ה אִתָּ֑ם (Exodus 12:38): a mixed multitude, a diversity of peoples journeyed with them. I would argue being in this room— whether Jewish yourself or supporting a Jewish loved one; whether as someone who has been coming for decades, or someone seeking and exploring being Jewish for the first time—if you are committed to the Jewish story, feel yourself flowing from the Jewish story, are supporting Jewish loved ones in the Jewish story—the Jewish story is your story; you have a stake in it. The Jewish Story is our story. Immersing ourselves in the Jewish story, if we understand it to be our story, helps us understand who we are, what our values are, and how we might carry out these values to repair this all-too-broken world.

For the remaining part of this sermon, I want to reflect, briefly, on what that story is, and what we might be able to take from it, recognizing that, as Jews, there are countless different versions of the story, and countless different interpretations.

I’ll offer two.

The first is what I’m going to call the “spiritual” version, and it goes something like this:

In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth, the earth having been unformed and void, and darkness having been upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters. And God said: ‘Let there be light.’ And there was light.

Thus the world was created as an act of the Divine will. Purposeful. Intentional. Holy. This, according to the Jewish story, is the beginning.

Upon the earth, humanity was fruitful and multiplied. Among the many people who populated the earth, the many human and divine relationships flowing on the earth, a relationship was formed between God and a man named Abraham. God, according to this story, called out to Abraham and said לֶךְ־לְךָ֛ Lekh-Lekha — “Go forth.” “Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” Abraham and his wife Sarah thus left the house of their parents to a new land, a promised land. God further said to them, “I will form a brit, a covenant between Me and you, and your offspring to come, as an everlasting covenant throughout the ages.” Thus, the Jewish story says that we are all heirs of Abraham and Sarah, carriers of that covenant, that articulation of an unseverable relationship to the Divine.

The story continues: through a combination of internal discord, and external pressures, the descendants of Abraham and Sarah found themselves descending into Mitzrayim, Egypt, the narrow place. There, we were subjected to oppression, constriction, subjugation, for many years.

Yet from that place of oppression we experienced the gifts of redemption. A man named Moses responded to God’s call to break us free from hardship, snapping victory from the jaws of defeat. As we sought to escape, just as the Egyptian army was barreling down on us, and the raging sea in front of us, the sea split, and we paraded forth to freedom, free to trek forward into the wilderness, come what may. We know freedom. We know hope can rise from the depths of despair.

What did come, what has come, according to the story, was the revelation at Sinai, a moment in which the Divine voice pierced through the normal quiet of human experience, its shock waves reverberating to this day. It is a revelation not only of Divine presence but of Divine Will, a Divine call: a call that the people embrace their — our — end of the bargain, our end of the covenant. The call said we had not not only freedom but obligation—obligation to act; to respond to myriad calls whereby we unleash holiness in the world: calls both ritual and moral in nature; from lighting candles on shabbat, signaling that creation, that life, culminates in rest, in peace; to loving and caring for the stranger, the refugee. We know what it means to be a stranger, and at Sinai we heard the call to act lovingly towards the strangers and refugees in the world. Not to demonize them. To receive them with love. These being just a couple of the 613 mitzvot, calls to action in our tradition. This covenant remains eternally binding. That is the ever-reverberating moment at Sinai.

From there we have experienced, throughout the generations, “the joys of homecoming, and the dislocations of exile:”¹ arrival at the promised land, breathing its air, tasting the fruits of its soil; and then exiles from it, being scattered about the earth, unmoored; all the while demonstrating resilience, creativity, imagination, rooted in our story, new branches growing.

The conclusion to the Jewish spiritual story? Though it is less familiar, there is one: that there will be a messianic resolution to the story, a redemptive resolution; that we will experience an age of redemption, bringing an eternal experience of shalom, wholeness, peace.

As Professor Elliot Ginsburg encapsulates it, the Jewish story “binds its adherents—us —in a web of faith and fate, memory and expectation, in a way that transcends the defining particulars of time and place.”

We may not be sure we “believe” all of the story in a literal sense and yet it travels with us as part of the Jewish experience. Part of life here at Society Hill Synagogue is to continue to form a relationship to this story, through coming together for Shabbat and Holiday services, through taking classes, learning its rhythms more deeply; through coming together to reflect and discuss and act, living out the values of the story. This is one version of the story.

But our story is not only a spiritual one; it is also a historical one. Not only one that transcends time, an eternity that came before us and that will follow after us; it is also very much one in time, forged in the alternatingly cold and warm lights of history.

The historical story doesn’t weigh in on whether a God spoke and called the world into being, or called forth to a man named Abraham and a woman named Sarah, or split the sea, or called out to the people at Mt Sinai to establish a covenant.

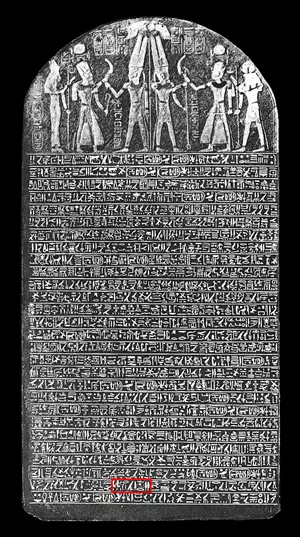

The historical story is presented in prose, not poetry. It begins with a single stone slab from the year 1207 BCE, This slab, known widely as The Merneptah Stele (pictured right) bears an inscription by the Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah, boasting that, during a military campaign in Canaan, the land corresponding to modern-day Israel, “Israel has been laid waste, his seed is not.” While this claim, as Mark Twain would say, proved to be greatly exaggerated, it serves as the earliest extra-biblical historical reference to the people of Israel and our story, over 3000 years ago.

The historical story is presented in prose, not poetry. It begins with a single stone slab from the year 1207 BCE, This slab, known widely as The Merneptah Stele (pictured right) bears an inscription by the Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah, boasting that, during a military campaign in Canaan, the land corresponding to modern-day Israel, “Israel has been laid waste, his seed is not.” While this claim, as Mark Twain would say, proved to be greatly exaggerated, it serves as the earliest extra-biblical historical reference to the people of Israel and our story, over 3000 years ago.

From there, historians are able to track the formation of two Israelite kingdoms by around 1000 BCE, Israel in the north, and Judah in the south.

In 722 BCE, the Assyrian Empire conquered and destroyed the northern kingdom, Israel, made up of ten of the twelve tribes, those ten tribes assimilating into surrounding peoples and becoming lost to history. In 586 BCE the Babylonian empire captured Judah and its capital Jerusalem, destroyed the temple, and sent most of its inhabitants into exile.

When Persia conquered Babylon 50 years later, it issued an edict allowing the Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem. Some do, having yearned for this, rebuilding the temple while under Persian rule; others do not, further developing Jewish life in the diaspora.

Soon it is Alexander the Great’s turn. He and his Hellenistic empire conquer the Perisan empire, and subsequent Hellenistic dynasties control the land.

All the while, Jewish life continues, through family life, through worship at the temple, through the interaction of Jewish and Hellenistic culture. The Passover Seder for example, was informed by the Greek Symposium, a Greek dinner and discussion format, this not being the last time that Jews and surrounding cultures were in conversation that each informed the other, often for the better, though which also required careful reflection about how the Jewish people could hold fast to its values and its identity and its story without being overwhelmed and lost to history.

Eventually, the Jewish freedoms were constricted in the now famous Hanukkah story. As we know, the Maccabees revolt, successfully overthrowing Greek rule, and establishing a new chapter of Jewish sovereignty.

It does not last long. Internal discord among Jews reigned, as a struggle for leadership succession broke out. Eventually Jewish leadership called in the newly ascendant Roman authorities to settle the dispute. In what amounted to letting the fox into the hen house, Rome established rule over Judea. The Jews revolted, leading to the Roman destruction of the second temple and the desolation of Jerusalem, ending, finally, any semblance of Jewish sovereignty in what is now known as Israel until the 20th century.

An end to Jewish sovereignty did not mean an end to Jewish peoplehood, however. Rising from the ashes of the destruction of the temple rose a new form of Judaism, what we call Rabbinic Judaism, in many ways similar to the Judaism that we know today—a Judaism expressed, rather than through sacrificial offerings at a temple structure, through prayer and study, ritual observance, and acts of lovingkindness.

By this point, the Jewish people had established communities throughout the Mediterranean and the near east, from Spain to Egypt; Morocco to Italy.

Finding themselves under both Christian and Muslim rule, depending on the year and location, the Jewish people experienced alternating periods of oppression and efflorescence; subjugation and rejuvenation. Yes there were the crusades, which led to attacks on Jewish communities in England, Germany, and France; and the Spanish inquisition, which expelled all Jews from Spain except those willing to convert. But this time period was also marked by the contributions of Jewish philosophers, scientists, poets, and theologians. From Maimonides to Nahmanides, Rashi to Isaac Luria, the Jewish people articulated new ways for Jews, and humanity, to understand God and life, justice and love. Jewish creativity and family life endured, both alongside hardship and within pockets of peace.

Eventually we reach what is known as the age of emancipation, in the 17- and 1800s. Until this point, Jewish living had largely been restricted to its own self governing communities, under the control of a larger empire. Once humanity reached the age of “enlightenment,” however, with strong beliefs in reason, scientific progress, and the capacity of all individuals to improve themselves, some societies began to push for the “emancipation” of Jews—the integration of Jews as citizens into their respective countries, calling upon Jews to leave behind all of the differentiating markers of their tradition (except those in their private spheres), instead becoming Frenchmen, or Englishmen, or, yes, Americans, as they began to reach these shores.

Of course as we know, history has never been a linear journey towards justice and peace. Subjugation of Jews—by this point known as antisemitism— did not go away with this renewed integration and modernity; in some respects it got worse. As historian Jon Efron writes, “In large measure, the modern period in Jewish history is characterized by the dynamic of, on the one hand, successful cultural, economic, and social integration,” see, for example, in many respects, 20th century Jewish American life, with thriving Jewish contributions to all sectors of society, while on the other hand, throughout the world “a backlash against those successes, producing social anxiety and hostility toward Jews.”

No moment more darkly typified the underbelly of this backlash than the lowest moment in Jewish — perhaps human — history: the shoah; the Holocaust. “The systematic state-sponsored killing of six million Jewish men, women, and children and millions of others by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II.”² The near total destruction of the Jewish communities of Europe.

No moment more darkly typified the underbelly of this backlash than the lowest moment in Jewish — perhaps human — history: the shoah; the Holocaust. “The systematic state-sponsored killing of six million Jewish men, women, and children and millions of others by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II.”² The near total destruction of the Jewish communities of Europe.

It’s a devastation we are still reeling from; Jews in the United States not unscarred by its occurrence: the failure of American institutions to do more to rescue Jews still weighing on our souls.

Prior to the Nazi Holocaust, An Austro-Hungarian Jewish Journalist, Theodor Herzl, held high hopes for what Jewish integration into mainstream society might look like. But over time he became disillusioned with that idea, and he became the modern founder of political Zionism, believing only a Jewish state for Jewish people — like a French state for French people and a German state for German people — could save the Jews from the demons of antisemitism.

After the Holocaust, the international community felt that it could no longer ignore what became known as “the Jewish question”, voting to partition what was then known as Palestine into two states: one Jewish and one Arab. By this point, waves of Jewish immigration had begun to repatriate the land, connecting with a small Jewish population which had remained there for millenia.

But this was by no means a land without a people for a people without a land. Arab people, too, had established communities by this point — as these waves of refugees encountered — and conflict was inevitable.

I needn’t recount the entire Israeli-Arab conflict; we are where we are today: a region torn by war and devastation: extremists on both sides declaring from the river to the sea this land is only for me, and my people.

Today, we inherit the legacy of this ongoing story, a story which can bear many different interpretations, one of which certainly involves a strong dynamic of Jewish life functioning both inside and outside the land of Israel, neither locale providing perfect peace and prosperity, the two serving in tandem to support one another.

The next chapter of this story is not yet written. That’s what’s up to us. That’s why my case for the importance of commiting to Jewish communal life at synagogues like Society Hill Synagogue has a third leg to its stool. Yes, it’s about community, forging bonds with one another, celebrating together in times of joy, being present to people in their times of sorrow. Yes, it’s about spirituality, holding space to wrestle with God, leaning on ritual and Torah as means of inviting an ongoing relationship to the divine into our lives, from which our actions might flow. But it’s also about our peoples’ story, a story whose roots, whose foundations, strengthen us as we reach out into the broader world. What does the next chapter of our people’s story hold? How can we help shape it?

It starts by showing up, in community, week after week, month after month, year after year; showing up with our minds, our hearts, our bodies, our souls, so that shofar can ring out, pure and true.

Shanah tovah.

Footnotes

¹ Elliot K. Ginsburg in his essay The Resonances and Registers of Jewish Myth written as a foreword to Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism by Howard Schwartz. My “spiritual version” of the story draws on this essay for inspiration.

² A definition shared by The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Encyclopedia Britannica

Tagged Divrei Torah, High Holiday Divrei Torah, Israel