As I’ve written about before, to be Jewish, to be in relationship to the Jewish people, entails a Jewish identity that is concerned not exclusively with traditionally “religious” considerations, but with the grand sweep of history, too: with the way in which the Jewish people and the loved ones in relationship with them find themselves caught up in, and actively engaged in, political and social developments throughout the course of history, in countries all over the world.

Political and social developments throughout history have deeply affected, sometimes for better, oftentimes for worse, the well-being of the Jewish people, and have deep impact on whether or not the values which the Jewish people hold dear are cherished. (There are many different interpretations on what these values are, but some of the more generally applicable ones include love for one’s neighbor and for the stranger; a desire to contribute to tikkun olam, repair of this broken world; the desire to provide tz’dakah to those in need; and many more.)

Political and social developments throughout history have deeply affected, sometimes for better, oftentimes for worse, the well-being of the Jewish people, and have deep impact on whether or not the values which the Jewish people hold dear are cherished. (There are many different interpretations on what these values are, but some of the more generally applicable ones include love for one’s neighbor and for the stranger; a desire to contribute to tikkun olam, repair of this broken world; the desire to provide tz’dakah to those in need; and many more.)

It is with this in mind that I reflect on the developments from yesterday’s historic election in the United States, the most powerful and influential country in the world, home to more Jews than any country in the world besides Israel, and home to our Society Hill Synagogue community.

The community of Society Hill Synagogue is not a monolith. There are stripes of many different political persuasions, and it is highly likely based on demographics alone that both major candidates received votes from members of this community. This is a diverse, pluralistic community, and one of the sacred elements of Jewish community is the capacity to speak and learn and hang in there within and across differences, showing up for one another without regard to political persuasion: at the shivah of someone who has lost a loved one and is grieving; at someone’s home, soup in hand, when someone is sick; at someone’s simhah, celebration, like B’nei Mitzvah or a wedding, helping someone experience joy in community. That remains a huge part of our community, within and across differences.

Still, I can also tell you that we have a number of congregants feeling very distressed by yesterday’s results. They have experiences similar to what I articulated in a recent D’var Torah: concerns for the rights of immigrants, who have been demonized and scapegoated over the course of this campaign and in years past — immigrants whose circumstances are not so different from the circumstances of the Jewish people from generations past, seeking a better life in a country of promise and possibility, escaping persecution and insecurity. Others are concerned that the bulwark of our democracy is not as strong as it once was. A Supreme Court decision last year changed the legal framework around a president’s immunity from prosecution, giving them more latitude to carry out acts that would have been unthinkable in the past.

Still, I can also tell you that we have a number of congregants feeling very distressed by yesterday’s results. They have experiences similar to what I articulated in a recent D’var Torah: concerns for the rights of immigrants, who have been demonized and scapegoated over the course of this campaign and in years past — immigrants whose circumstances are not so different from the circumstances of the Jewish people from generations past, seeking a better life in a country of promise and possibility, escaping persecution and insecurity. Others are concerned that the bulwark of our democracy is not as strong as it once was. A Supreme Court decision last year changed the legal framework around a president’s immunity from prosecution, giving them more latitude to carry out acts that would have been unthinkable in the past.

And yet we are also no stranger to adversity. No chapter of Jewish or human history has been without its challenges. If there is anything consistent about Jewish existence, perhaps it is endurance, creativity, and rootedness in the face of adversity.

There remain many action steps that concerned citizens can take in the face of what they may see as an administration not aligned with their values: support of a robust free press through subscriptions and other means; support of organizations dedicated to protecting civil liberties here in the United States, working in the courts to ensure our rights are protected; support of organizations advocating for immigrants’ rights; and so much more. We have been here before, time and again, and collectively, small acts make a huge difference.

Furthermore, much which is sacred takes place outside of the explicitly “political” arena. The first thing I did today outside of the home was encounter a Playschool teacher preparing to care for the many children whom they were to support today. Each of us brings so much value to the world on a day-in-day-out basis, of which we and the world barely take note. This is not an exhortation to abandon the political arena or to suggest it doesn’t matter. Rather it is to remind ourselves that on a daily basis. we bring so much goodness into the world. Taking note of the many small ways we provide that goodness is sacred.

Finally, I wouldn’t be a rabbi if I didn’t believe in the power of spiritual nourishment that comes from living within the rhythms of Jewish life. The lessons of Jewish living long precede — and I would argue will long outlast — many of the challenges we face today. There is something to be said for attuning ourselves to the rhythms of the Eternal, not only (though certainly also not instead of) the day-to-day grind. This includes opening ourselves up to prayer, giving ourselves space to imagine what can be and finding the inspiration to pursue it; coming together on Shabbat, a sacred day of rest and rejuvenation, in community, learning, praying, and dining together; and finding time for classes and social action and social activities in community that are rooted in timeless Jewish values.

Finally, I wouldn’t be a rabbi if I didn’t believe in the power of spiritual nourishment that comes from living within the rhythms of Jewish life. The lessons of Jewish living long precede — and I would argue will long outlast — many of the challenges we face today. There is something to be said for attuning ourselves to the rhythms of the Eternal, not only (though certainly also not instead of) the day-to-day grind. This includes opening ourselves up to prayer, giving ourselves space to imagine what can be and finding the inspiration to pursue it; coming together on Shabbat, a sacred day of rest and rejuvenation, in community, learning, praying, and dining together; and finding time for classes and social action and social activities in community that are rooted in timeless Jewish values.

There are so many avenues of life that can bring us meaning as we nourish and support ourselves alongside the work that needs to get done. I am holding you in my heart, mind, and spirit as we continue the ongoing work of building community.

This past Shabbat, prior to the election, I delivered the following D’var Torah. While my words did not have the election in mind, they do speak to hope in the face of adversity:

We Jewish clergy make a lot of the fact that the Jewish month we just completed, Tishrei, has many holidays — here at Society Hill Synagogue, in fact, we held 18 services over the course of one month — and that the next month, Marheshvan, has none.

Except, that’s not entirely true. The Ethiopian Jewish community celebrates a holiday known as Sigd at the end of the month, but it’s actually not even true for every Jewish community, and that’s because we’re celebrating a different Jewish holiday, right here and right now. No, I’m not talking about Shabbat. Although, yes, that, too. I’m talking about Rosh Hodesh. The head, the beginning, of a new month.

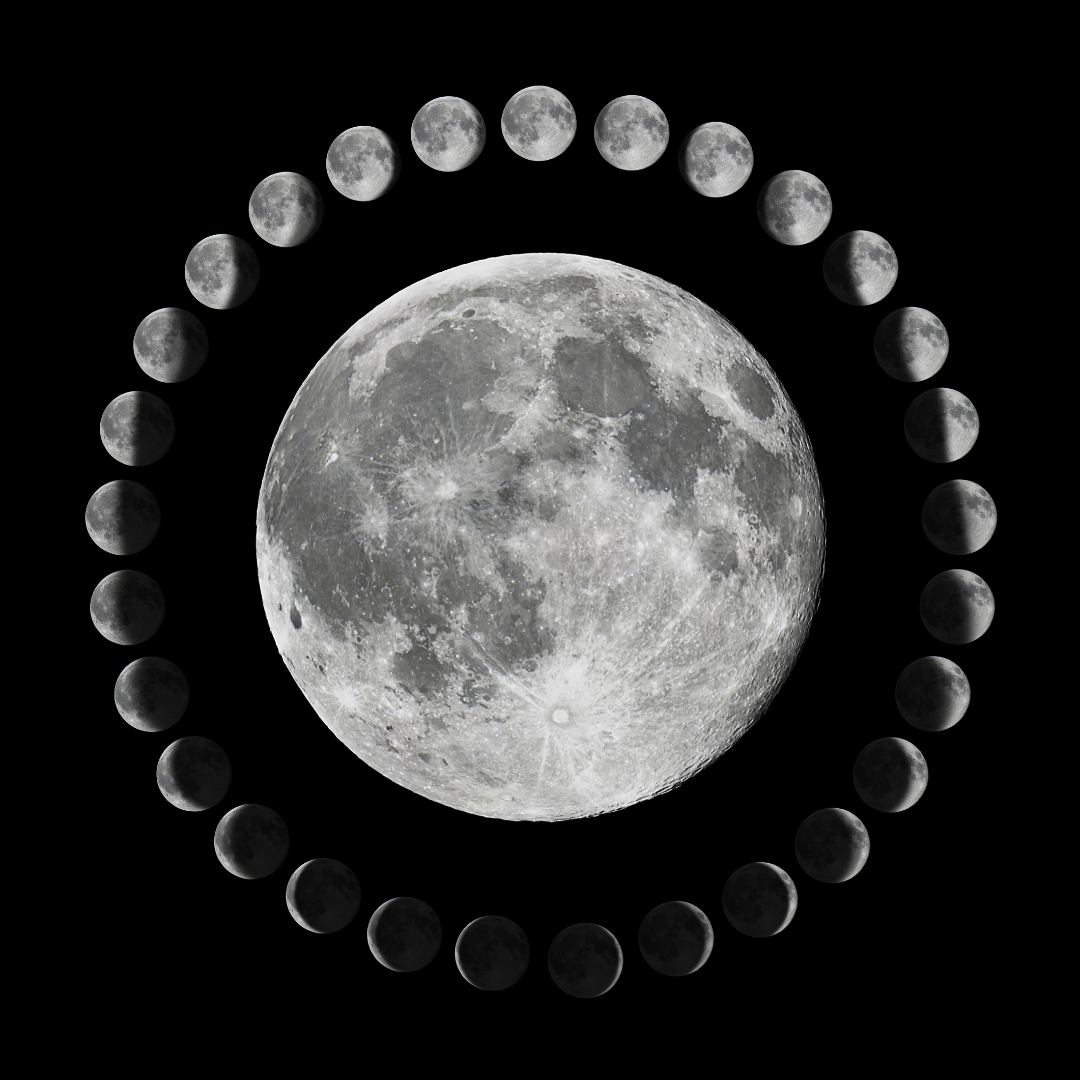

As many of you know, the Jewish calendar is tied in part to the moon. The moon waxes and wanes over the course of a month. It waxes: it gets brighter and brighter, fuller and fuller, until it reaches a full moon. Then it begins to wane: it diminishes, or at least our ability to see it does, as it shrinks and shrinks, until it is essentially imperceptible. We can’t see it even if there were no buildings, no city lights obfuscating our view. The moon is, for all intents and purposes, gone. Then, just as the moon is at its darkest, just as it has reached essentially invisibility, it begins to grow again, to glow again, and that is Rosh Hodesh, the moment that the moon’s darkening has crested and it begins to grow and glow all over again.

As many of you know, the Jewish calendar is tied in part to the moon. The moon waxes and wanes over the course of a month. It waxes: it gets brighter and brighter, fuller and fuller, until it reaches a full moon. Then it begins to wane: it diminishes, or at least our ability to see it does, as it shrinks and shrinks, until it is essentially imperceptible. We can’t see it even if there were no buildings, no city lights obfuscating our view. The moon is, for all intents and purposes, gone. Then, just as the moon is at its darkest, just as it has reached essentially invisibility, it begins to grow again, to glow again, and that is Rosh Hodesh, the moment that the moon’s darkening has crested and it begins to grow and glow all over again.

So what is the Jewish significance of this moment? And why, if it is so significant, do we not know more about it?

Most of us reach Jewish adulthood without knowing much about Rosh Hodesh. We know it is tied to the moon. Some of us know there are additional prayers we say. But it’s missing many of the rituals we’re used to in Jewish life that really make a holiday stand out. No special candle lightings, no special foods, no, at least at first glance, special stories.

Modern traditions have cropped up. Groups exploring Jewish femininity, like ours at Society Hill Synagogue, have formed to celebrate and reflect during Rosh Hodesh. Our group met for the second time this past Sunday.

But somehow, as a larger community, we’ve become disconnected from the sacred origins of the holiday, which is on the short list of holidays listed in the Torah at which special offerings were brought to the sanctuary.

So what are those origins, and what meaning can we make of the holiday today?

Looking at the verses from Torah which call upon us to bring that special offering on Rosh Hodesh, the new moon, today, it says the following:

This shall be the monthly burnt offering for each new moon of the year.

Zot olat hodesh b’hodsho l’hodshei hashanah.

זֹ֣את עֹלַ֥ת חֹ֙דֶשׁ֙ בְּחׇדְשׁ֔וֹ לְחׇדְשֵׁ֖י הַשָּׁנָֽה׃

And there shall be one goat as a sin offering for Adonai.

Us’ir izim ehad l’hatat la’Adonai

וּשְׂעִ֨יר עִזִּ֥ים אֶחָ֛ד לְחַטָּ֖את לַיהֹוָ֑ה

A sin offering for Adonai. This phrase had the rabbis puzzled. On the one hand, what is religion if not apologizing, making amends, for our sins. We’re Jews; we’re always feeling guilty about something. What’s another sin offering? But that’s not what this special offering for Rosh Hodesh says. It says a sin offering for Adonai, on behalf of Adonai. It’s the only time in the Torah that phrase is ever used. Rosh Hodesh is the one day we make a sin offering, for, on behalf of, God.

What does that mean? What did God do wrong?

A midrash teaches that when God first created the universe, God created the sun and the moon to be the same size. In Bereshit, Genesis, chapter 1 it says:

God made the two great lights

Vaya’as Elohim et-shnei hame’orot ha’gdolim

וַיַּ֣עַשׂ אֱלֹהִ֔ים אֶת־שְׁנֵ֥י הַמְּאֹרֹ֖ת הַגְּדֹלִ֑ים

No suggestion about differences in size. But, the Talmud teaches, the moon complained. “Master of the Universe,” the moon said. “Is it possible for two kings to wear the same size crown?” The Holy One answered the moon. But as you can guess, it was not what the moon wanted. “Go, then, and make yourself smaller,” God said to her. Thus it says, at the end of that same verse from Genesis, God made the two great lights:

The greater light, the sun, to dominate the day and the lesser light, the moon, to dominate the night.

Et-hama’or hagadol l’memshelet hayom v’et-hama’or hakaton l’memshelet halailah.

אֶת־הַמָּא֤וֹר הַגָּדֹל֙ לְמֶמְשֶׁ֣לֶת הַיּ֔וֹם וְאֶת־הַמָּא֤וֹר הַקָּטֹן֙ לְמֶמְשֶׁ֣לֶת הַלַּ֔יְלָה

The moon responded: “Master of the Universe, since I said a correct observation before You, must I diminish myself?” God said to her: “Alright. As compensation, go and rule both during the day, along with the sun, and during the night. You will sometimes be able to be seen by day, too.” She said to God: “What greatness is there in shining alongside the sun? What use is a candle in the middle of the day?” God said to her: “Very well; in addition, the Jewish people shall count the days and years with you, the moon will be a central part of their calendar, and this will be your greatness.” But, she said to God: “the Jewish people will count with the sun as well; the Jewish calendar is tied to both the moon and the sun.”

God saw that no matter what God did, God could not comfort her. So The Holy One, Blessed be God, said, as written in the Torah, “Bring atonement for me,” since I diminished the moon.

God saw that no matter what God did, God could not comfort her. So The Holy One, Blessed be God, said, as written in the Torah, “Bring atonement for me,” since I diminished the moon.

And every Rosh Hodesh, the priests would bring a hatat la’adonai, a sin offering on behalf of God.

So what does this teach us, and how might it invite us to approach and to commemorate Rosh Hodesh?

On one level you might say, of all the things for God to regret — hunger, war, suffering, pain — the sin offering brought on behalf of God is for God’s diminishment of the moon?

And yet the suggestion here is that perhaps the new moon is a signal — like the rainbow is a signal in this week’s Torah portion, Noah — that each month, on Rosh Hodesh, on the new moon, we’re invited to consider that God, too, has regrets; that in this covenantal relationship between humanity and the divine, God, too, aches with pain for God’s part of the relationship; aches for the distance, the chasm in the relationship, offering an expression of regret to reopen the pathway to reunion.

The new moon each month, Rosh Hodesh, is a reminder to us of God’s taking ownership of God’s part in the distance of the relationship, inviting us to return. And of course this happens at a moment during the course of the month when the relationship might feel at its lowest ebb. The moon is a symbol of the sh’hinah, the most accessible level of the divine presence, also the feminine aspect of the divine presence. And Rosh Hodesh is commemorated, on the one hand when that presence is least apparent, when the moon is least visible.

And yet also at the exact moment when the moon is commencing its return, when we begin to reunite.

And, of course, the moon never actually leaves, even if it isn’t always visible to us in the same way. Like God, the moon is never any nearer to us or further from us than at any other point in time. It never leaves its orbit around the earth. The moon’s visibility is instead dependent upon our perspective. From certain angles — certain relationships between the earth, sun, and moon — it can feel fully present; from others, it can feel fully absent. It’s a matter of perspective. And yet it is always there, in the same way.

And, of course, the moon never actually leaves, even if it isn’t always visible to us in the same way. Like God, the moon is never any nearer to us or further from us than at any other point in time. It never leaves its orbit around the earth. The moon’s visibility is instead dependent upon our perspective. From certain angles — certain relationships between the earth, sun, and moon — it can feel fully present; from others, it can feel fully absent. It’s a matter of perspective. And yet it is always there, in the same way.

So, too, with God. God, according to Jewish tradition, is always fully present. But there can be moments in our lives where we can really feel that absence.

Rosh Hodesh is symbolic of the moment of deepest longing, the sense of absence, even when the presence is really there. The Zohar, the central text of Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism, teaches that the mashiah, the messiah, the figure who will one day initiate the age of redemption, the age when peace and justice will reign and relationships between all parents and children will be healed, the mashiah dwells in Gan Eden, the Garden of Eden, waiting for that age of redemption. On Rosh Hodesh, the Zohar teaches, at the new moon, the mashiah can hold in his longing for redemption no longer, and he lifts up his voice and lets out a deep cry; a sob.

Rosh Hodesh is symbolic of the moment of deepest longing, but also of deepest hope, because that is the moment when God and the mashiah reconnect. God hearing the cries of the mashiah, reassuring him that the promises of redemption will indeed be fulfilled in time to come.

Sometimes, Jewish tradition teaches, the greatest sense of distance can prompt the greatest sense of yearning, a yearning whose very essence leads to a sense of reunion, eliciting a sense of hope, and indeed of faith.

Wishing you a hodesh tov, a good month, one of hope, one of faith, and one of peace.

Shabbat Shalom.

Rabbi K.

Tagged Divrei Torah