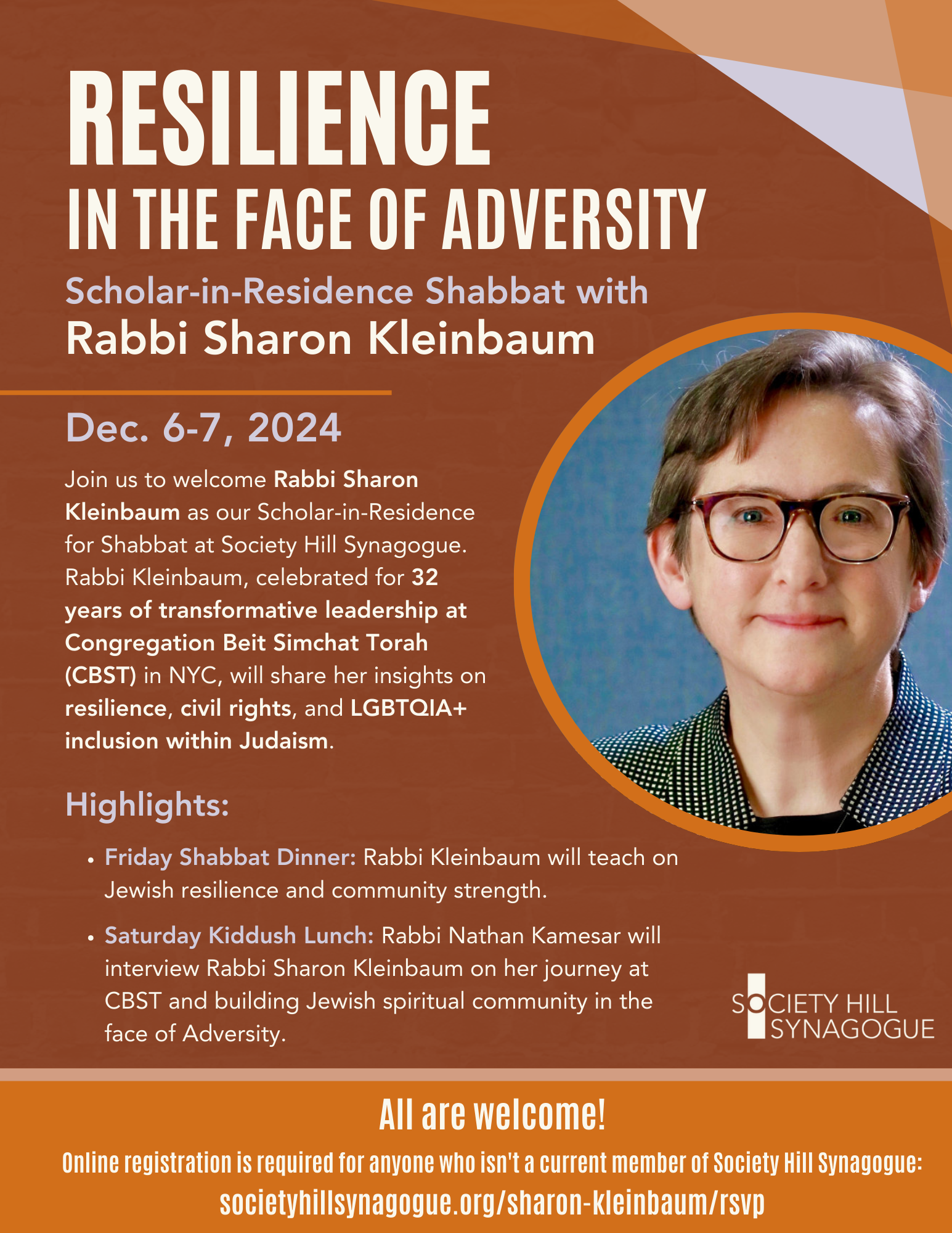

First of all, I want to make sure you mark your calendars for the Shabbat of Friday evening, December 6 and Saturday morning, December 7, when a friend and teacher of mine, Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, will be the Scholar-in-Residence at Society Hill Synagogue.

First of all, I want to make sure you mark your calendars for the Shabbat of Friday evening, December 6 and Saturday morning, December 7, when a friend and teacher of mine, Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, will be the Scholar-in-Residence at Society Hill Synagogue.

Rabbi Kleinbaum was CBST’s first staff member, brought in when the community had a far more modest footprint, and in the midst of the worst moment of the AIDS crisis when the community was experiencing pain and heartache on a regular basis. As CBST’s website states “a lethal combination of viral illness and anti-Gay bigotry left the community perpetually caring for its sick and dying, mourning its losses, and comforting those left behind.” Through Rabbi Kleinbaum’s tender pastoral guidance and spirit of resiliency, the community survived and thrived.

Many years later, thanks to a gift to the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, by Bill Fern, a congregant Rabbi Kleinbaum served at CBST, the Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum Congregational Internship was established, affording area synagogues the opportunity to bring in rabbinic interns. In 2014, that opportunity was granted to Society Hill Synagogue. It was Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum Congregational Internship that first brought me to Society Hill Synagogue in 2014; I have served this community ever since, first as Rabbinic Intern, then as Associate Rabbi, now Rabbi, the professional blessing of a lifetime.

The connections continue: Rabbi Kleinbaum was classmates and friends with my father and with Society Hill Synagogue Rabbi Emeritus Avi Winokur, and our mutual affection remains significant.

There couldn’t be a better time — or a more relevant topic — around which to have Rabbi Kleinbaum speak to this community. Rabbi Kleinbaum’s career has been marked by a true spirit of resiliency. She brings a deep sense of hope and optimism to the conditions she and her community have encountered, while remaining grounded in the hard realities that make that optimism so difficult.

She will speak to us about the way those sensibilities, rooted deeply in Jewish tradition and teachings, speak to this moment. So many of us feel the adversity of this moment, whether driven by painful worldwide episodes of antisemitism, changing political terrain that leaves many of us fearful of what comes next, or by personal experiences of adversity — addiction, family struggles, loneliness and isolation.

Rabbi Kleinbaum’s brand of frank reflection about the realities with which we’re confronted, paired with a natural hopefulness that speaks to a redemptive Jewish spirit, is just the right teaching for this moment. I’m so grateful she’ll be joining us.

Please be sure to register!

What follows is the D’var Torah (teaching of Torah) I delivered this past Friday night, which coincided with the Bar Mitzvah celebration of Society Hill Synagogue member Daniel Weinstein and family:

We encounter a lot of different liturgy over the course of a daily or Shabbat service, and yet there is perhaps no passage that is more subtly controversial than one we just encountered on as we prayed silently just now.

Not only found in this service, but actually traditionally chanted three times a day, every day in Jewish communities all around the world, it is the second blessing of the Amidah. The Amidah is the central t’filah, prayer, of Jewish worship. It echoes the ancient korbanot, sacrificial offerings, which had the effect of inviting people to feel the nearness of God — korban comes from the word to draw near — and also serves as the avodat ha’lev, the service of the heart, pouring out what was on our hearts over the course of this offering.

When the earliest rabbis debated and shaped Jewish religious expression into the forms which we still know today, they moved from free-flowing spontaneous liturgy to specifically prescribed texts in order to facilitate communal cohesion. The knowledge that Jewish people in each community say the same prayers, across far-flung regions, in the midst of the diaspora and exile, facilitated a sense of resilience and togetherness.

The set blessings that these rabbis established for the Amidah began with blessings of awe. The first blessing, known as Avot, ancestors, expresses a sense of awe to God for the brit, the covenant established with our ancestors, continuing to us and beyond into an era of redemption.

But the controversy doesn’t pick up until the second blessing of awe known as gevurot — strength — which will be our focus this evening.

It begins straightforwardly:

You are ever mighty, Adonai.

Atah gibor l’olam Adonai

אַתָּה גִּבּור לְעולָם אֲדנָי

Thus far, nothing controversial. In fact that’s about as boilerplate a phrase as one can imagine in a religious prayer book. And yet the very next phrase, the first illustration by the rabbis of God’s might, reaches the controversy that the Jewish people are still grappling with to this day:

You give life to the dead, great is your saving power

Mehayeh metim Atah

מְחַיֵּה מֵתִים אַתָּה

It continues, “You cause the wind to blow and the rain to fall, You sustain the living through kindness and love and…” — here it is again,

You are ever mighty, Adonai.

Mehayeh metim b’rahamim rabim

אַתָּה גִּבּור לְעולָם אֲדנָי

…You support the falling, heal the sick, loosen the chains of the bound, and keep faith with those who sleep in the dust. Mi Kamokha, Who is like You, Almighty, and who can be compared to You…

The sovereign who brings death and life, and causes redemption to flourish

Melekh memit um’hayeh, umatz’miah y’shuah

מֶלֶךְ מֵמִית וּמְחַיֶּה וּמַצְמִיחַ יְשׁוּעָה

And, lest the rabbis think we might have missed the central theme of this blessing, how do they choose to end it?

You are faithful in bringing life to the dead:

Blessed are You Adonai, who gives life to the dead.

V’ne’eman Atah l’hahayot metim:

Barukh Atah Adonai, mehayeh hametim.

:וְנֶאֱמָן אַתָּה לְהַחֲיות מֵתִים

:בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יי, מְחַיֵּה הַמֵּתִים

Just the part we always lead with when we’re explaining Judaism to our non-Jewish loved ones, right? “We Jews regularly thank God for giving life to the dead!”

Ok, so let’s take a moment: what is this, and what do we do with it?

Let’s start with the historical. The authors of these prayers, the ancient rabbis, very much had as a part of their discourse a doctrine known as tehiyat hametim, the resurrection of the dead. Biblical and rabbinic writings are rarely, if ever, systematic in terms of how they lay out belief systems. Oftentimes, they do more to preserve disagreements about key theological questions than they do to harmonize and proliferate one specific belief, preferring instead to preserve a system of ongoing dialogue and debate.

The same is true for beliefs about the afterlife: there is no singular systematic presentation in any ancient text of what the Jewish belief is about what happens to us when we die.

Still, there are many references to different beliefs, and a central one became this idea of tehiyat hametim, that when we die, our soul survives, eventually reaching Gan Eden, the garden of eden, paradise, and at the end of days, in the age of messianic redemption, we would all experience tehiyat hametim, the resurrection of the dead, body and soul would resurrect together.

As proof for this belief, they would cite various passages from scripture, including, for example, the following verse from the prophet Isaiah which says:

Oh, [Eternal One] let Your dead revive! Let corpses arise! Awake and shout for joy, You who dwell in the dust! — For Your dew, [Eternal One,] is like the dew on fresh growth; You make the land of the shades come to life.

Yih‘yu meteyah n’velati y’kumun hakitzu sh’kh’nei afar ki tal orot tale’ah va’aretz r’fayim tafil

יִֽחְי֣וּ מֵתֶ֔יךָ נְבֵלָתִ֖י יְקוּמ֑וּן הָקִ֨יצוּ וְרַנְּנ֜וּ שֹׁכְנֵ֣י עָפָ֗ר כִּ֣י טַ֤ל אוֹרֹת֙ טַלֶּ֔ךָ וָאָ֖רֶץ רְפָאִ֥ים תַּפִּֽיל

Perhaps because of this central belief in ancient times, every time we come to a service — a service celebrating someone in our community becoming Bar Mitzvah, a Shabbat service, a personal prayer service chanted three times daily — we come across these words.

So how do we encounter these? What do we take from them when we leave a prayer experience?

Lately, when I encounter this phrase, mehayeh hametim, a phrase which can be translated in a number of different ways, I think it about it less on a theoretical level — what happens to human beings after they die — and I more think about in on a personal level: hametim, those who have died: mahayeh, You keep them alive.

I feel their presence with me, my own personal loved ones. I think about my father, whose yartzeit, the anniversary of whose death is this week, and I say thank You, God. You keep our loved ones’ presences alive.

This can be interpreted on a metaphorical level: the memories of them, the ways in which they’ve inspired us, impacted us, are very much alive within us.

But as should be clear by now, despite what we may have previously understood, Judaism very much makes space for this on a metaphysical level, too. That is, thank you God, for keeping our loved ones’ presences literally alive. I can feel their spirit, I can feel his spirit. Thank you for that, God, for giving me an understanding: that on one level, yes, death is an end, but that on another level, life transcends that. Thank you for allowing me to feel, sometimes palpably, the presence of my loved ones, what they might say to me at a given moment.

If this sort of spirituality doesn’t work for you, there are more naturalistic ways to interpret this blessing. Marcia Falk, a renowned Jewish poet and liturgist, writes the following: “To celebrate life is to acknowledge the ongoing dying and ultimately to embrace death. For although all life travels towards its death, death is not a destination: it too is a journey to beginnings: all death leads to life again. From peelings, to mulch, to new potatoes, the world is ever-renewing, ever-renewed.” God, factually speaking, brings all death back to life.

And, lest we think this sort of thinking was only available to moderns, the ancient rabbis, too, understood that not all passages were meant to be interpreted literally.

The rabbis had blessings for so many things we encounter on a regular basis. A blessing upon seeing the ocean, a blessing upon seeing a rainbow. A blessing upon hearing good news, a blessing upon hearing bad news. A blessing for any number of noteworthy occurrences that might take place over the course of a day, including a blessing upon seeing someone for the first time in over a year. And what did they say for that blessing? Baruch Atah Adonai, blessed are You Adonai, mehayeh hametim — who revives the dead. They understood this phrase did not have to be interpreted literally. They deployed humor and irony and hyperbole in language both sacred and mundane.

Mehayeh hametim to the Hasidim, to mystics, may have been about spiritual revivification: my spirits were downtrodden, I was depressed; thank you God… mehayeh hametim, the One who has given me a new sense of life, who has brought me back from the spiritual doldrums. We can interpret it that way, too.

Finally, as relevant to someone about to celebrate becoming Bar Mitzvah, and to his parents, at a sacred moment in life where we reflect on the moment where responsibility for mitzvot, for sacred actions, shifts from parents to child, one way of understanding mechayeh hametim, bringing life to the dead, is that it is a blessing thanking God for creating a world where our life has significance that transcends our time on this terrestrial earth.

A teaching about life beyond death is a teaching that, as Rabbi Lawrence Hoffman writes, in one way or another, our life has eternal value and we’re called upon to live so that we affirm that value daily. Barukh Atah Adonai, thank You God, who creates life with eternal significance.

That is, in essence, what it means to become Bar Mitzvah, it means there is a sense of sacred responsibility that we’re called upon to bring to the world, a responsibility that, when fulfilled transcends even our time here on earth.

Wishing you a sense of the eternal.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi K.

Tagged Divrei Torah