The other night I was reading my four and a half year old daughter Lila a bedtime story. We have a routine that she gets to watch two music videos and read three stories before bed (I spoil her, I know).

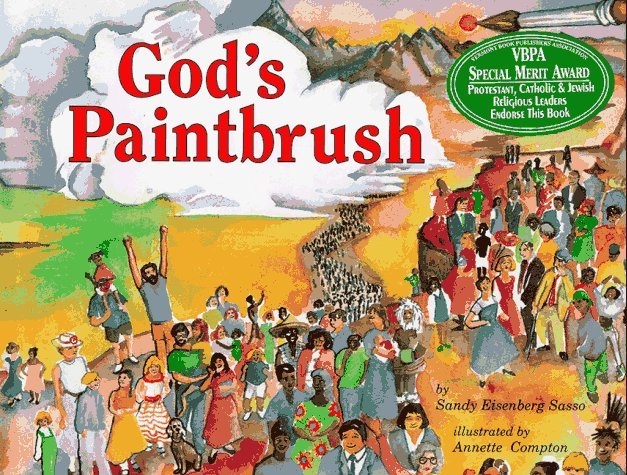

So we’re on our fifth and final piece of content for the evening when she pulls out God’s Paintbrush by Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso. It’s the book we give to all kids here at Society Hill Synagogue in honor of their baby namings, and which she received for her own baby naming four years ago, and yet, I’ve never really read it closely.

The book is written from a child’s perspective, imagining how their own life might be similar to, or different from, God’s.

“Sometimes,” one page begins, “I like to play hide and seek with my friends. We count to ten and then start looking.” Standard hide and seek rules. “But today, my friends got tired of looking, and went away before they found me. I felt very lonely.

“On Monday,” it continues. “I broke my mom’s vase. I was scared. I hid behind the large sofa in our living room. Mom came home. I was glad when she found me. I felt lonely all by myself.

“Sometimes,” the child narrator says, “I think God hides, and we don’t want to look for God, because we are too busy or too afraid. God must feel terribly lonely then, too.”

“I think God hides, and we don’t want to look for God, because we are too busy or too afraid.”

Too busy to look for God hits way too close to home.

I’m a rabbi. It’s my literal job to cultivate a relationship to the sacred so that I can help others do so, too, and yet I feel like I allow my 21st century life to keep me too busy to look for God sometimes. Between emails and texts pinging, phones ringing, news notifications going off 24/7, it’s no wonder we can feel a sense of overwhelm.

Add into that caring for kids, or grandkids or elderly parents, centering your partner in your life, tending to the demands of your job—where does anyone find the time?

And yet I believe it is so important to, as this child says, look for God, and one way of underscoring the importance of this is to imagine God yearning to be looked for. Imagine ourselves yearning to be looked for and then imagining that experience within God, too.

In his tome Man Is Not Alone, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel has a chapter called “The Hiding God.” He writes, “we live in an age when most of us have ceased to be shocked by the increasing breakdown in moral inhibitions…” in 1951. “Good and evil, which were once as distinguishable as day and night, have become a blurred mist. But that mist is man-made. God is not silent. God has been silenced.”

Heschel goes on to use the imagery of hiding. “It is not God who is obscure. It is man who conceals Him. His hiding from us is not in His essence: “Verily Thou art a God that hidest Thyself, O God of Israel, the Saviour! (Isaiah 45:15). A hiding God, not a hidden God. He is waiting to be disclosed, to be admitted into our lives.”

Waiting to be disclosed, to be admitted into our lives.

Now, Heschel makes it sound like this is easy, and in a sense, he suggests, it is:

“Our task is to open our souls to Him, to let Him again enter our deeds. We have been taught the grammar of contact with God; we have been taught by the Baal Shem that His remoteness is an illusion capable of being dispelled by our faith. There are many doors through which we have to pass in order to enter the palace, and none of them is locked.”

We’ve got to pass through some doors, but they’re not locked.

What does this mean?

To return to our child narrator, the narrator says, ““I think God hides, and we don’t want to look for God, because we are too busy or too afraid.”

You may have a different “too.” Too indifferent? Too skeptical? Too numb? For me, the “too busy” resonates deeply. That is my obstacle right now.

A different sage, educator, author Stephen Covey, teaches the wisdom of recognizing the difference between the urgent and the important. Our emails, our phones, our notifications can feel urgent—we feel like we need to respond right away to everything pinging in our inbox. Often that which is urgent, or that which we perceive as urgent, crowds out that which is important.

How do we carve out time for the things that are so important, but which, unless we treat them differently, will never take on a sense of urgency.

For me, that’s prayer, exercise, or reading a good book. The things which nourish my mind, body, and soul.

For Heschel, it’s letting God into our lives. Seeking God out, not just expecting God to intervene.

“A hiding God, not a hidden God. God is waiting to be disclosed, to be admitted into our lives…. Our task is to open our souls to Him, to let Him again enter our deeds.”

Even in the course of all the business of our lives, our caring for family, our tending to our work responsibilities: can God be present there, too? Where in those everyday interactions can we let God in, can we invite God out of hiding?

For Heschel the stakes are high. The very moral foundations of the world depend on our ability to do so.

But even on a more personal level, the difference can be meaningful. Rabbi Jacob Staub shares his theology when he writes, “I don’t believe that God decided to cause the sun to rise this morning. I don’t believe God watches over my children and makes them mature. I don’t believe God solves my work problems. But I do believe I live in a world that God underlies and suffuses. I do believe that I do not generate my virtuous deeds and insights independently, but rather am connected to a greater Source of strength and blessing with whom I am always trying to align. I believe some things are right and some things are wrong, and I believe that when you do the wrong thing you are opposing the divine will and that the world is so constructed that you will suffer for it internally.”

In other words this task of letting God in, of seeking God out, can have reverberations externally and internally. For Heschel it’s the very moral state of the world; for Staub it’s the misalignment we feel when we do the wrong thing.

As this child imagines it, there God sits, hiding, alone. What would it mean for us to dedicate ourselves to finding God?

Wishing you holiness on your search.

Tagged Divrei Torah