Erev Rosh Hashanah 5785

I want to start my teaching this evening with one of the most well-worn stories of the Yamim Noraim, the Days of Awe, about a boy and his flute.¹

When Rabbi Israel was about to enter into his synagogue in Medziboz, he stopped outside the door and said, “I cannot go in there; there is no room for me.”

“But,” his students said, “There are not many people in the synagogue.”

The rabbi responded, “The house is filled from the ground to the roof with prayers! There is no room for me to enter.”

When Rabbi Israel saw that his students were excited by this proclamation, he said, “You don’t understand. Those prayers have no strength to fly to heaven. They are struggling, stuck, and the house is filled with them.”

And he returned home, unsure of how to make these prayers fly.

Not far from Medziboz there lived a Jewish herdsman. This man had an only son. The boy was twelve years old but struggled to learn, and could not remember the alphabet. For several years the father had sent his son to school, but as the boy could not remember anything, the father ceased to send him, and instead sent him into the fields to mind the cows.

There, the boy took a reed and made himself a flute, and sat all day long in the grass, playing upon it.

But when the boy reached his thirteenth birthday, his father said, “After all, he must be taught some shred of Jewishness.” So he said to the lad, “Come, we will go to the synagogue for the holidays.”

He got in his wagon, and drove his son to Medziboz, and bought him a cap and new shoes. And all that time, David carried his flute in his pocket.

His father took him to the synagogue of Rabbi Israel.

They sat together among the other men. The boy was very still.

Then the moment came for the prayer of Musaf, the late morning prayer, to be said. David saw the men all about him raise their little books, and read out of them in praying, singing voices. He saw his father do as the other men did. Then David pulled at his father’s arm.

“Father,” he said, “I too want to sing. I have my flute in my pocket. I’ll take it out, and sing.”

But his father caught his hand. “Be still!” he whispered. “Do you want to make the rabbi angry? Be still!”

David sat quietly on the bench.

Until the prayer of Minhah, the afternoon prayer, he did not move. But when the men arose to repeat the Minhah, the boy also arose. “Father,” he said, “I too want to sing!”

His father whispered quickly, “Where have you got your fife?”

“Here in my pocket.”

“Let me see it.”

David drew out his fife, and showed it to his father. His father seized it out of his hand. “Let me hold it for you,” he said. David wanted to cry, but was afraid, and remained still.

At last came the prayer of N’ilah, the closing prayer of the Days of Awe. The candles burned trembling in the evening wind, and the hearts of the worshipers trembled as the flames of the candles. All through the house was the warmth of holiness, and the stillness as before the Presence.

The boy could hold back his desire no longer. He seized the flute from his father’s hand, set it to his mouth, and began to play his music.

A silence of terror fell upon the congregation. Aghast, they looked upon the boy; their backs cringed, as if they waited instantly for the walls to fall upon them.

But a flood of joy came over the countenance of Rabbi Israel. He raised his spread palms over the boy David.

“The prayers are free!” cried the Rabbi “returning to their Source in the Holy One, connecting us all.”

Each Erev Rosh Hashanah, it feels important to me to point out that over the next ten days or so, we are going to be spending a lot of hours in services like this one. In fact if my math is right, and it maybe isn’t, there are approximately 20 hours of communal prayer over the course of the six services of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

That’s a lot of time spent doing something that I would argue we all have a pretty mysterious relationship to, a complicated relationship, a relationship without a lot of clarity, and that thing is of course tefilah, prayer.

Now, some of you might argue, that’s not exactly what all of us do when we are here. Yes, ostensibly, we are all praying, in the sense that the clergy are up on the bimah leading us in prayer, and so, indisputably prayers are being chanted in this room.

But that doesn’t mean each of us considers ourselves to be praying. Some of us are simply sitting here, letting the words, the melodies, wash over us. Maybe singing along from time to time when it’s a tune we know, maybe looking around at the people around us; maybe staring out the windows — we’re just being; just existing; in community; in the rhythms of the Jewish year, as Jews have done for millenia.

To that I say, yes. Absolutely. Amen.

Like this little boy chiming in with his flute, your occasional Amen, a word which might as well be pronounced, “I’m in,” as in, “count me in, even if I didn’t sing or say every word that was uttered, even if I was just sitting here letting my mind, my heart, my spirit wander” — your presence here helps lift up our prayers; the mutuality of affirmation contributing to the sacredness of the experience, and contributing further the collective efficaciousness of our prayers.

So, your presence is enough, your “amen” is enough.

Still, we’ve got a lot of time here together, a lot of precious, sacred time. So each year on Erev Roshanah, at the beginning of that time, I think it’s worth reflecting on the mindset we bring to this time here together, the heartspace in which we enter it — worth reflecting on what each of our respective approaches to prayer is, and then, ideally, worth reflecting on whether or not we might bring that sensibility not only to the synagogue space, to the sanctuary during the holidays or Shabbat, but to the mikdash m’at, the smaller sacred spaces we each create for ourselves — our houses, our homes, whatever corners of the world we encounter throughout our years in between the High Holy Days. Perhaps the sensibility we bring to prayer here, may in fact have a role there, too.

What is prayer? Let’s start there.

I have been in Jewish community for all 41 years of my life; I started rabbinical school eleven years ago; I’ve been a full-time rabbi for six of those years. And I am still figuring out my relationship to prayer.

Most days, I set aside an hour for prayer: half an hour in the morning after I drop my daughter off at school before I start my work day, a luxury perhaps easier for a rabbi than for some of you; that’s shacharit, the morning prayer. I then try to find 15 minutes before I leave my office for the day, the afternoon mincha prayer, though if I’m being honest, that’s the one I most often fail to make happen. And then 15 minutes after my last committee meeting for the evening, the evening prayer of ma’ariv, like the one we’ve nearly completed here tonight.

By now, I am deeply familiar with the traditional liturgy, and so I spend part of my time during each sitting going over the most traditional prayers in the service—the shema and its blessings, the amida—and part of my time, just in quiet, talking to God, or thinking, inviting God to be present to my thoughts.

Is this prayer?

I think so. I’m still not sure.

I’m reminded of one of the bevy of parenting books I read before my older daughter Lila was born, this one called The Gardener and the Carpenter, by the Philadelphia-born Jewish professor of philosophy and psychology, Alison Gopnik. She describes two possible metaphors for the work of being a parent: one the carpenter; the other the gardener. Arguing that many of us think that the way parenting works is like carpentry, she describes that as follows: under the carpenter model, “you believe that essentially your job is to shape the material into a final product [i.e., the child] that will fit the scheme you had in mind to begin with. And you can assess how good a job you’ve done by looking at the finished product. Are the doors true? Are the chairs steady? Messiness and variability,” she continues “are a carpenter’s enemies; precision and control are her allies. Measure twice, cut once, as the saying goes.” Just make sure you do it exactly right, and you’ll get the result you want. That’s the work of a carpenter, and, she suggests, how many of us initially approach parenting, imagining if we are determined enough, precise enough, thorough enough, we will produce children exactly to the specifications we first imagined.

I’m reminded of one of the bevy of parenting books I read before my older daughter Lila was born, this one called The Gardener and the Carpenter, by the Philadelphia-born Jewish professor of philosophy and psychology, Alison Gopnik. She describes two possible metaphors for the work of being a parent: one the carpenter; the other the gardener. Arguing that many of us think that the way parenting works is like carpentry, she describes that as follows: under the carpenter model, “you believe that essentially your job is to shape the material into a final product [i.e., the child] that will fit the scheme you had in mind to begin with. And you can assess how good a job you’ve done by looking at the finished product. Are the doors true? Are the chairs steady? Messiness and variability,” she continues “are a carpenter’s enemies; precision and control are her allies. Measure twice, cut once, as the saying goes.” Just make sure you do it exactly right, and you’ll get the result you want. That’s the work of a carpenter, and, she suggests, how many of us initially approach parenting, imagining if we are determined enough, precise enough, thorough enough, we will produce children exactly to the specifications we first imagined.

As any parent knows, that’s exactly how it goes, right?

Not so much.

Instead, she writes, a better metaphor for a parent than a carpenter is a gardener. “When we garden,” she writes, “we create a protected and nurturing space for plants to flourish. It takes hard labor and the sweat of our brows, with a lot of hard digging and wallowing in manure. And,” she continues, “as any gardener knows, our specific plans are always thwarted. The poppy comes up neon orange instead of pale pink, the rose that was supposed to climb the fence… stubbornly remains a foot from the ground; black spot and rust and aphids can never be defeated.”

“And yet,” she continues, “the compensation is that our greatest… triumphs and joys also come when the garden escapes our control, when the weedy white Queen Anne’s lace unexpectedly shows up in just the right place in front of the dark yew tree, when the forgotten daffodil travels to the other side of the garden and bursts out among the blue forget-me-nots, when the grapevine that was supposed to stay demurely hitched to the arbor runs scarlet riot through the trees.”

Now, while I have barely the gardening skills to keep a cactus alive, I can tell you that, as with gardening, so, too with prayer.

We don’t know how to produce an exact desired outcome. We don’t know how to precisely pull on the exact right internal or cosmic strings in order to yield a desired result. When it comes to prayer, we are not carpenters.

But we can open some space, till some soil, get our hands dirty, and see what grows.

In fact, to the extent there are necessary ingredients that can be identified for a successful prayer experience, which it’s hard to say with certainty that there are, but if there are, one of them, I would argue, is this very act of giving up any desire for a predetermined outcome. Rather, the success of the prayer experience is very dependent, I believe, on suspending our preconceived judgments about what we think is right, about how it’s supposed to go.

There is an even shorter story I love to share on this topic: A man determined that he wanted to be “enlightened.” So he goes to the famous Zen master and explains his desire. Not necessarily expecting a direct answer, he asks the Zen master, “how long will that take me? The Zen master pauses, thinks about it, and says “ten years.” “Ten years?!” the man exclaims. “But what if I try really hard? The Zen master pauses, and considers, and gives his answer: “Twenty.”²

There is an even shorter story I love to share on this topic: A man determined that he wanted to be “enlightened.” So he goes to the famous Zen master and explains his desire. Not necessarily expecting a direct answer, he asks the Zen master, “how long will that take me? The Zen master pauses, thinks about it, and says “ten years.” “Ten years?!” the man exclaims. “But what if I try really hard? The Zen master pauses, and considers, and gives his answer: “Twenty.”²

In most experiences we’re trying to exert our will; in prayer we’re trying to yield it.

What does this look like?

Again, I don’t know. This is not “measure twice, cut once.” This is, “just do it.”

In fact, as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel says, the very essence of prayer is that we don’t know what we’re going to say. We just say it. Blurting out whatever is in our heart in the presence of the Holy One, offering it up

Articulating the differences between prayer and speech, he writes, “The purpose of speech is to inform; the purpose of prayer is to partake.” “In speech,” he says “the act and the content are not always contemporaneous. What we wish to communicate to others is usually present in our minds prior to the moment of communication.” We often think generally about what we’re going to say before we say it. “In contrast,” he writes, “the actual content of prayer comes into being in the moment of praying.” Yes, some of our prayers are written down in the prayerbook, and we’ll return to that in a moment, but we’re also invited, while we’re in this space, while we’re at home, to just open up our hearts, open up our mouths, and see what comes out.

Similarly, Rebbe Nachman of Breslov describes how to approach this sort of prayer. We just begin to think, to talk, to feel, in the presence of God.

“Even if a person is totally and absolutely distant from God’s service” he teaches “that person should speak about it all and seek understanding in relation to God.” “God, I’m not totally sure what to say,” we might begin. “I’m not even sure I believe in you,” we might say. That is all fair game. “But,” we might continue, “I yearn to do what is right, I yearn to understand more than I know, I yearn to open up to experience beyond myself, grateful as I am for the blessings in my life, for the blessing of life.

“Even if a person is totally and absolutely distant from God’s service” he teaches “that person should speak about it all and seek understanding in relation to God.” “God, I’m not totally sure what to say,” we might begin. “I’m not even sure I believe in you,” we might say. That is all fair game. “But,” we might continue, “I yearn to do what is right, I yearn to understand more than I know, I yearn to open up to experience beyond myself, grateful as I am for the blessings in my life, for the blessing of life.

“Even if occasionally a person’s words are sealed and he cannot open his mouth to say anything at all to God, this itself is nonetheless very good,” Rebbe Nachman teaches. “That is,” he continues, “a person’s readiness and a person’s presence before God, and a person’s yearning and longing to speak despite their inability to do so—this in itself is also very good. It is possible to make a conversation and prayer out of this itself.” A person should cry out and plead to God about this very thing,” he concludes, “that he has become so distant he is unable to even speak.” This, too, is prayer.

Now how, you might ask, does this sort of prayer—pouring out whatever is on our hearts— correspond to what we are holding in our hands, the mahzor, the prayer book, with its pages and pages of prescribed liturgy.

I recently taught a class on prayer, and I asked the class the very same question I’m asking here tonight — what is prayer? — and I got two answers: (1) “talking to God.” We’ve begun to cover that. The other answer? (2) the ongoing liturgy of the Jewish people as formulated over time in our prayer books. Prayer, in this sense, is communal. As Michael Fishbane writes, “In Jewish prayer the Jewish person evokes the memories and hopes of past and present Jewish communities as part of a living minyan, a living prayer community.” We open ourselves up not only to our own experience, but to the experience of others, past, present and future, feeling strengthened through the collective hum reverberating across time.

And in the same way the gardener is excited to see what blooms, the gardener knows there has to be a level of discipline to ensuring her plant life is taken care of.

Rebbe Nachman, who preaches the virtues of spontaneous prayer, calling out whatever is on our heart, also calls for discipline in setting aside time to pray, and the fixed times for traditional prayers can serve as those times.

Furthermore, the suggestion goes, the content of the traditional liturgy, for many, serves not only as a source of connection to others praying, but as words that invite us down pathways our heart didn’t know it needed to go. Vessels which point our heart in the direction of worlds unconsidered.

The two — spontaneous prayer and traditional liturgy — can serve as partners on the map of the soul.

To paraphrase Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, Traditional liturgy, the prayer book, can be the “container of the life of the spirit,” the verses serving as vessels for what our heart needs to say but doesn’t have the words. “The soul’s most profound experiences with a presence greater than the self,” she continues “are given form and articulation through liturgy… Liturgy, in turn, she suggests, “remain[s] constantly open to the renewal of sacred moments.” Each word in the prayer book can be invested with our own lived experiences.

“If spirituality, ” she continues, the freewheeling expression of the spirit — “at its best lifts us up, religion” — traditional liturgy — “ at its best keeps us rooted.”

The one can inspire the other, two pathways to a Divine encounter.

One final story.³

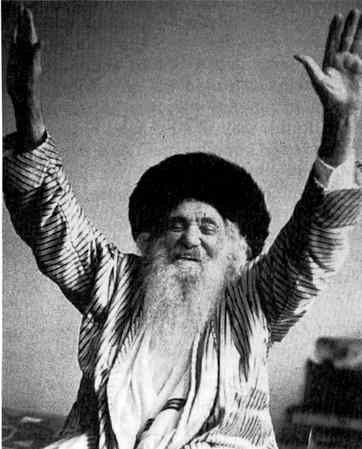

“Rosh Hashanah will soon be upon us,” said the Baal Shem Tov, the mysterious Jewish mystic, to his disciple, Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf, “and I want you to prepare the traditional prayers that one must concentrate upon for the blowing of the shofar.” You’re going to be the one to sound the shofar this year, and I want you to make sure you know the proper, mystical meditations to concentrate upon before sounding it.

R’ Ze’ev studied the various meanings and hidden connotations of all the prayers for sounding the shofar, writing these all down for reference on Rosh Hashanah. He placed his list in a coat pocket and considered himself prepared. But this form of preparation did not satisfy the Baal Shem Tov so he caused the list to disappear.

When R’ Ze’ev approached the platform to perform his duties on Rosh Hashanah he suddenly discovered his loss. His mind was now a blank as to which prayers he must chant, and his heart was broken within him. Breaking into bitter sobs, he was forced to perform his task unprepared.

After the services the Baal Shem Tov called him over and said: “In the king’s palace there are many doors and portals, each one with a key of its own. There is, however, one tool which can open all of them; that is the axe. The tefilot, the berakhot, the traditional prayers which you learned, are the keys which open the gates of heaven, each gate having its own particular key, its own particular prayer. But a broken heart is a tool which can penetrate all the gates and palaces of heaven.”

We’ve got both tools with us, tonight, and wherever we go.

We have the keys — we have our tradition, we have our liturgy, we have our prayer book; and we have the axe — our heart, our soul, maybe even a flute.

Ketivah v’chatima tovah; May you experience a good inscription and sealing in the Book of Life.

Shanah Tovah.

Footnotes

¹ This version of the story is lightly adapted from the story “The Boy’s Song” presented by Meyer Levin as found in The Yom Kippur Anthology: A JPS Classic edited by Phillip Goodman.

² Adapted from a footnote by Barbara Briteman as found in A Guide to Jewish Practice: Everyday living edited by David A. Teutsch.

³ Lightly adapted from a story presented by Alan Lew in his famous High Holiday book This Is Real And You Are Completely Unprepared