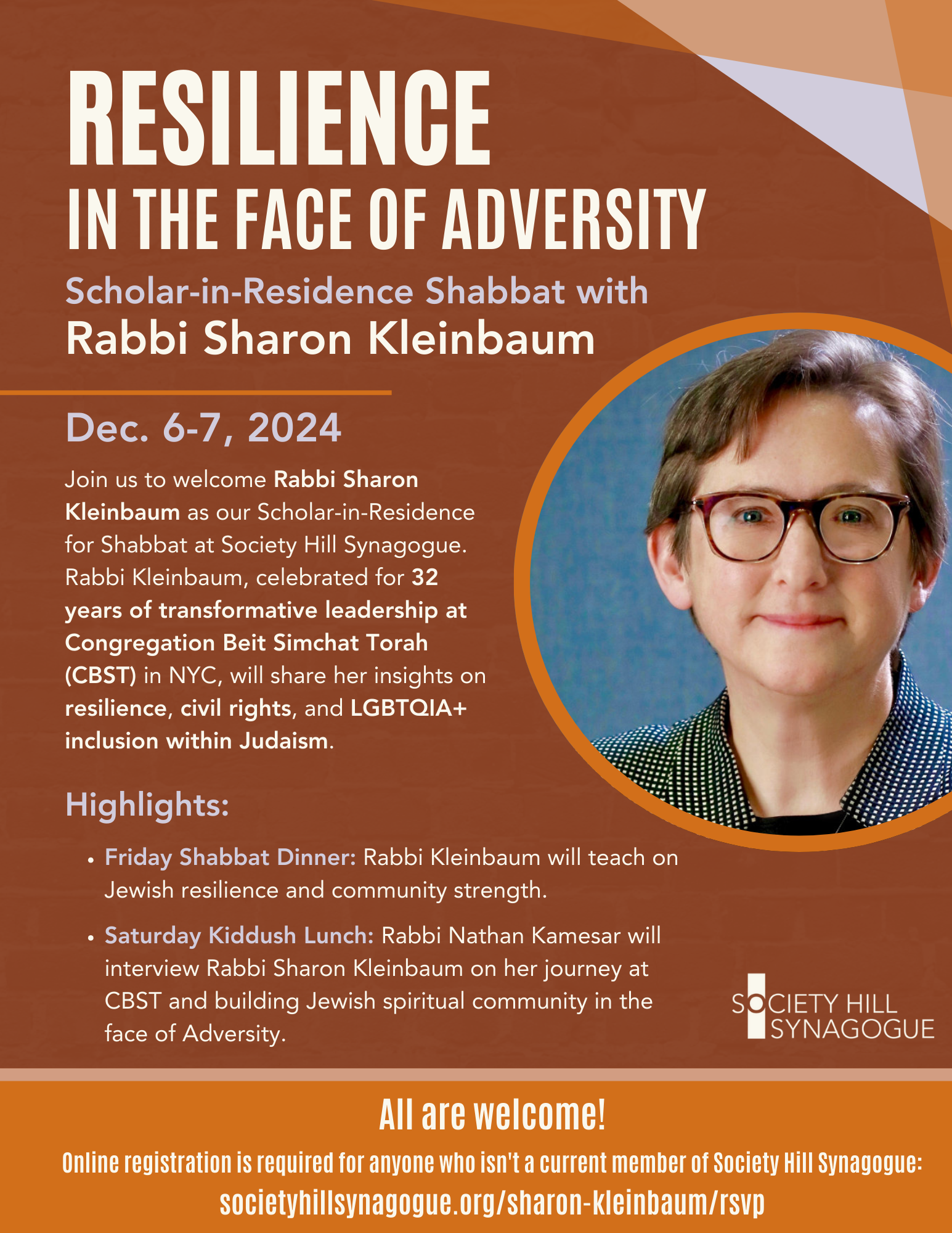

I am very excited that this week we are welcoming Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum to our community as Scholar-in-Residence. To me, she is a teacher, role model, and friend. Her arrival comes on the heels of her being named this week to the BBC’s 100 Women: the BBC’s list of 100 inspiring and influential women from around the world in 2024, and she is one of only seven Americans to be named to the list. (Three Israelis were also named.) It’s an honor to have Rabbi Kleinbaum join us this coming Shabbat.

I am very excited that this week we are welcoming Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum to our community as Scholar-in-Residence. To me, she is a teacher, role model, and friend. Her arrival comes on the heels of her being named this week to the BBC’s 100 Women: the BBC’s list of 100 inspiring and influential women from around the world in 2024, and she is one of only seven Americans to be named to the list. (Three Israelis were also named.) It’s an honor to have Rabbi Kleinbaum join us this coming Shabbat.

What follows is the D’var Torah I delivered on November 22, coinciding with the celebration of Brayden Goldstein’s Bar Mitzvah:

Recently, I taught a class. That’s part of my job as a rabbi, to teach a lot of classes to adults exploring their relationships to Judaism, to being Jewish, to asking what our rich, sacred inheritance, evolving as it has over the years, has to offer us in this moment, living as we are at the intersection of antiquity — a timeless search for meaning rooted in an ancient era — and modernity, living in a fresh age with new insights, new technologies, new instincts.

Recently, I taught a class. That’s part of my job as a rabbi, to teach a lot of classes to adults exploring their relationships to Judaism, to being Jewish, to asking what our rich, sacred inheritance, evolving as it has over the years, has to offer us in this moment, living as we are at the intersection of antiquity — a timeless search for meaning rooted in an ancient era — and modernity, living in a fresh age with new insights, new technologies, new instincts.

Sometimes, if I may say so myself, these classes sparkle. Participants leave with ways of looking at the world like they haven’t before, or at least haven’t in a long time. I’ve prepared in such a way that the class allows for a balance of spontaneity and structure — space for participants to bounce new ideas off of one another, while also keeping the class guided, and at a forward moving pace. Like I said, sometimes the class experience really shines.

And sometimes, like this class, they really don’t. That doesn’t mean nobody gets anything out of it; I’m sure they do. It’s not every day we’ve carved out time in our lives to wrestle with how Jewish tradition can play a role in our lives, so sometimes a class that I may not think went very well does indeed plant a seed that gives someone something to chew on. But nonetheless, sometimes I leave a class that I’ve taught and think, “man, that really left something to be desired. I did not prepare for that in the way I really needed to. That did not flow how I planned; I could have done more.”

I wish I could say this experience was relegated to classes I taught, and not also for sermons I deliver, prayers I lead, meetings I run, conversations I have. And yet it is true for all of them.

Time and again, in work or life, I will experience something I prepared for and leave the experience with the feeling that I could have or should have prepared differently, harder, more thoughtfully. I could have done more.

It’s that feeling, that pang of regret, that I want to talk about for the moment.

It’s that feeling, that pang of regret, that I want to talk about for the moment.

I want to go out on a limb to say that we all have pangs of regret in life — and I’m not even talking about big life choices, grand moral dilemmas; I’m talking about our day-to-day responsibilities; day-to-day interactions. The kids today call it “cringe.” Oh man, I made that choice, I chose to say that in response, I thought that would be enough for that session?

What I want to reflect on for a moment is the Jewish response to that experience.

It’s not unrelated to the experience of becoming Bar Mitzvah, when we’re coming up on the bimah, on the stage to perform for the first time certain Jewish rituals reserved exclusively for Jewish “adults” aged 13 and above. Our Bar Mitzvah has been preparing for a long time, and yet inevitably if not with this then with something else, there will come a moment when he’ll say, whoops — that could have gone differently, that could have gone better.

So what does Judaism say about that pang?

In short, Judaism calls it shayarei zimrah, which translates to something like, “the remnants of a melody” or “that which is left over after singing” and it says that God finds favor in it, a connection to God is found in it, in the pang.

What do I mean by this?

In the closing blessing to P’sukei D’zimrah, the verses of song with which we open up every Jewish morning prayer service, including the one tomorrow for Brayden’s Bar Mitzvah, the blessing concludes with the words, “barukh Atah Adonai… haboher b’shirei zimrah.” Blessed are You Adonai, who delights in shirei zimrah. “Shirei zimrah” literally means something like, “melodious song.”

In the closing blessing to P’sukei D’zimrah, the verses of song with which we open up every Jewish morning prayer service, including the one tomorrow for Brayden’s Bar Mitzvah, the blessing concludes with the words, “barukh Atah Adonai… haboher b’shirei zimrah.” Blessed are You Adonai, who delights in shirei zimrah. “Shirei zimrah” literally means something like, “melodious song.”

The rabbis, however, never ones to gloss over any passage in sacred text, say something doesn’t quite make sense about that phrase, something doesn’t check out. Primarily, they say, it’s what scholars Nehemia Polen and Rabbi Lawrence Kushner call a pleonasm, a fancy word word which means “redundant” — using too many words to convey a certain meaning. Shirei zimrah — you find favor God, in shirei zimrah, in songs that are song-like. Shir and Zemer, both words essentially mean the same thing, and so it’s a phrase that doesn’t make sense.

Instead, a couple of Hasidic rabbis say, the blessing is being pronounced wrong. If you change the vowels — which is very plausible to do in Jewish tradition, since the Hebrew language is often passed down without vowels, and the vowels might have been misapplied — if you change the vowels, it would be shayarei zimrah, which means “the remnants of a melody” or “that which is left over after singing.” God, You find favor in the remnants of a melody; in that which is left over after singing.

So what do I mean by this, and how does this connect to the pangs of regret we feel after a mistake, a cringeworthy experience of a performance? What the Hasidic rabbis, such as Zev Wolf of Zhitomir or Simcha Bunim of Peshischa, say this speaks to is whatever is leftover in our hearts after we’ve sung our hearts out. That that’s where God finds us. Inevitably, there is something left over after singing, even when we’re supposed to have tried to sing our hearts out, and that’s where God finds us, and we find God. This blessing comes at the end of the morning service when we’ve been called upon to do a lot of singing, and it says, God, thank You. You find favor in the part of my heart that’s still there, that’s leftover after trying to pour it all out.

A different metaphor from this, for a sports fan like Brayden and the Goldstein family, is leaving it all out on the field. That’s what we try to do as an athlete; we say, I left it all out on the field. I gave it my best.

A different metaphor from this, for a sports fan like Brayden and the Goldstein family, is leaving it all out on the field. That’s what we try to do as an athlete; we say, I left it all out on the field. I gave it my best.

But it’s never entirely all out on the field. There’s always something still inside us. A little bit left over. That’s what God connects to. After we’ve tried. After we’ve put it out there. After we’ve made ourselves vulnerable to the possibilities of coming up short, and we inevitably, as we do in life, do indeed come up short — shayarei zimrah — that leftover ounce of song still in our heart, that is, as Jewish tradition says, where we can find God and God can find us.

So after a class, after a performance, after a Bar Mitzvah celebration, after all the efforts we make in life that inevitably leave just a little bit to be desired, I say “barukh Atah Adonai,” blessed are You Adonai, “haboher bashayarei zimrah” — you find favor in the remnants of a melody, in what’s left over after singing.

Thank you for finding me, and for loving me, there too.

Wishing you all a Shabbat of love; Shabbat Shalom.

Rabbi K.

Tagged Divrei Torah